Setbacks and Failures Befall the Underwater Detectives

Peter Wytykowski had waited a year for this moment. As a participant in the third international expedition to the wreck of the escort destroyer ORP Kujawiak, he had another chance to dive on the beloved ship.

Wytykowski led the 2015 expedition, code-named “L 72, A Forgotten Tragedy”, in which he and his teammates dived to a depth of 100 meters and examined the wreck. He was the first human to see the wreck in all its glory since it had sunk 73 years prior. It was a very special moment for Wytykowski.

Last year, he brought aboard the white and red flag of Poland, which fluttered on the ship for a few minutes after being absent for decades. He promised that the association would affix the flag to the wreck permanently when they returned.

June 9, 2016, was to be the first and long-awaited day of diving on the wreck of the ORP Kujawiak in search of the ship’s bell. On the quest for “the heart” of the destroyer escort were Peter Wytykowski and Mark “Sharky” Alexander of the United States, and Mark “Jonesy” Jones from England. The first disappointment had come the day before, when the team arrived on site only to discover that their mooring line had disappeared under the waves. With a new, temporary line in place, the team now located its marker upon arrival at the site, only to find it straining under prohibitively strong sea current. Unfortunately, this current would delay the hunt for the precious artifact once again. The atmosphere was tense among the friends as diving was postponed for the next day. This was not the end of problems they were to face.

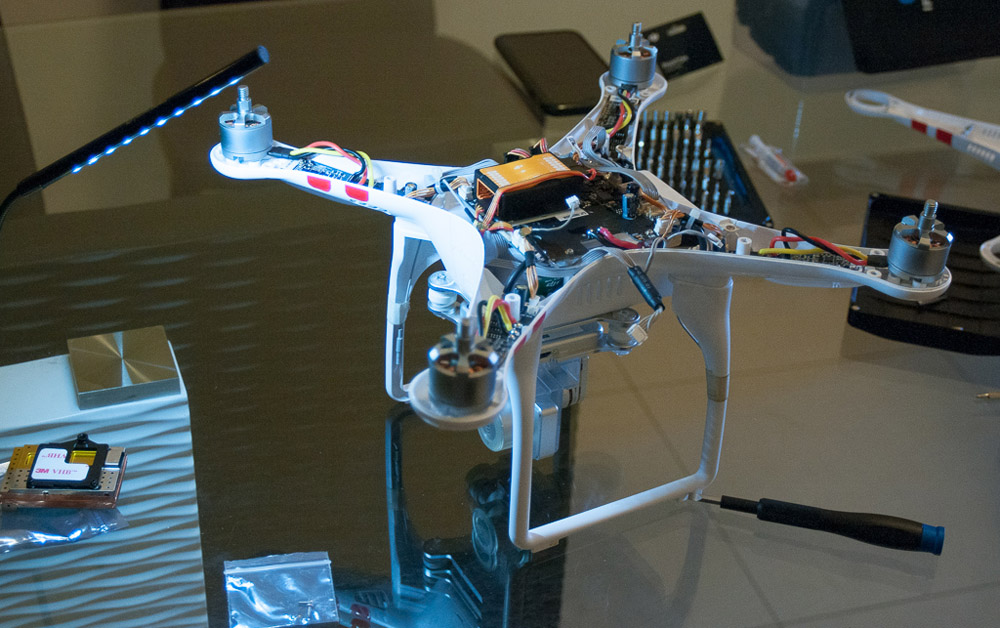

Even before heading out to sea, the team had discovered that the airborne drone they had taken on the expedition, was faulty. Although capable of flight, it was incapable of transmitting or recording video. For the better part of a day, it threatened to put an end to their hopes of obtaining the aerial video footage documenting their trip to Malta. Expedition members Scott DellaPeruta from the US and Robert Pias from Lodz eventually diagnosed the problem and located replacement parts at an independent service center in Malta.

The Maltese showed great professionalism and support, quickly delivering the needed electronic components and even lending tools so that the divers could perform the installation and adjustment on their own.

On June 10, the ocean currents at the wreck site were again quite strong, but not enough to discourage the divers from descending to the wreck. They finally began searching for the bell.

The original location of the ship’s bell had been ascertained with the help of documentation and archival photographs of Type II Hunt-class escort destroyers provided by Mariusz Borowiak, author of the book “Underwater trackers: The secret of the wreck of the destroyer escort ORP Kujawiak.” Photo survey evidence from the first expedition to the wreck site had shown that all that remained was the mount to which the bell was attached. It was possible that the bell broke away during or after the sinking from the force of the explosion near the ladder. This is one of the hypotheses. It was also possible that, in the passage of time, the iron mount corroded and the brass bell fell somewhere in the vicinity of the wreck. Only after an extensive search — and perhaps a bit of luck — might the truth be known.

For this day, the truth remained hidden. The strong current was slowing the divers’ descent to the wreck, cutting into their precious “bottom time” and limiting the search to less than 20 minutes for the day. With the next stage of the search, combined with a mission to affix the flag to the ship and with the added payload of bulky cinematic camera equipment, scheduled to take place on June 11, they had to find a way to avoid the currents and extend the available bottom time on this next descent.

June 11, 4:00 am: Roman Zajder, president of the Shipwreck Expedition Association, and Mariusz Borowiak ordered a wake-up call for their colleagues. They had decided that they should reach the wreck site as early as possible in the hope that ocean currents would be more favorable, allowing more time for mission operations, including the search for the bell.

There was again much tension among the teammates; conditions were not much more favorable, but they finally they were able to dive. The search team planned for a total dive time of over two and a half hours with a bottom time of about 25 minutes and the bulk of the remainder being spent on the much longer decompression and return to the surface. Well known Italian diver and photographer Gianmichele Iaria, a participant in the expedition, recorded the moment Peter Wytykowski affixed the flag to the ship.

The scene as the flag began to “wave” on the ship was poignant. Jonesy and Sharky then swam to the flag and the latter, a veteran of the US Army, gave a salute in honor of the fallen. Finally, the search for the bell was resumed over an expanded area.

For several days, a dark cloud had hung over the members of expedition “Heart of L72”. There was nervousness within their ranks. Had the streak of good luck, which had blessed the previous two expeditions, come to an end? After two days of problems preventing the divers from reaching the wreck, and two days of difficult and limiting conditions spent searching for the bell with no result, members of the international expedition were now being forced to spend the next two days on land due to high winds. The skipper did not want to expose the crew to danger and feared that the bad weather could cause their boat to capsize. Expedition goals are second in priority to safety; loss of human lives would put a quick end to any hope of results. Still, members of the expedition worried and anxious about the days to come.

While forced to remain in port, the divers used their time to meet with the ICEX research team. The six students from California Polytechnical Institute and Harvey Mudd College, and their leader, Dr Christopher Clark, Director of the Lab for Autonomous and Intelligent Robotics (LAIR) at Harvey Mudd, are studying underwater archaeology and performing side-scan sonar studies in collaboration with the University of Malta to collect data for their Intelligent Shipwreck Mapping with AUVs project. Members of the L72 team prepared an audiovisual presentation of their current project as well as several years of the activities of the Shipwreck Expedition Association’s achievements as “underwater detectives” in search of wrecks.

The presentation was led by Peter Wytykowski, Mark “Sharky” Alexander and Scott DellaPeruta. The ICEX team were also treated to a private screening of the English-language version of the documentary, “Mystery of L72,” which is included with the book, “Undersea Detectives,” by Mariusz Borowiak and was met with teary eyes and applause. The students had a lot of questions for us, as did we about their fascinating projects. We were mutually impressed! Contact information was exchanged with the hope of cooperation in the future.

The next land-bound day found the divers visiting the Maritime Museum in Valletta. With the help of Dr. Timmy Gambin from the University of Malta (one of the greatest authorities on underwater archeology in the Mediterranean and a friend of the Association), they enjoyed a behind-the-scenes tour of the museum’s warehouses and renovation workshops in addition to the permanent exhibition.

June 15: It was another chance for the search beginning with a 5:00 am wake-up. The weather was good for diving but the mood among the team members was less than optimistic. Not only was time running out for the expedition, but hardware failures were beginning to haunt us in earnest. It turned out that the repair of the drone had been only partial. Is GPS was not working reliably. Without GPS, it would be extremely difficult for the operator to hold position in these windy skies, rendering it effectively useless. Even more seriously, one rebreather had been damaged at the end of the prior dive; we managed to obtain a replacement in time for this day’s mission. On the water this day, a support diver experienced a failure of a dive computer. And now, once again, there were problems finding the mooring.

Its buoy had filled with water and had partially sunk in the current. Many passes over the area revealed fleeting glimpses of the buoy. Safety officer Steve Wilkinson showed his watermanship skills not for the first time this expedition, leaping into the water multiple times to track the buoy along with the chase boat.

Finally, expedition leader Roman Zajder donned open circuit gear and attempted a free descent down-current onto the submerged mooring. Impressively, the two met at a depth of 30 meters. He managed to surface dragging the free end of the line, requested another to be thrown from the main boat, and tied us in. We were on the wreck, but this had been another costly waste of time and the surface current was now literally ripping.

Disappointment struck again just as the search team was preparing to enter the water: a search diver reported a serious failure of his own rebreather electronics, which had tested perfectly just minutes beforehand, and had to “call” his dive. The search for the bell would have to be undertaken with a smaller team. Moreover, the loss of a diver required a rapid re-assessment of breathing gas contingency plans. The safety team discussed reallocating cylinders to compensate while Peter asked the unavoidable questions: “Was fate against us today? Had there been too many failures?” There is a point at which the cumulative mental stress of problem solving, delays, and last-minute plan alterations conspire with challenging water conditions to practically guarantee additional failures and mistakes. That point was hauntingly coming into view.

The fully suited team — sitting and standing on the boat laden with hundreds of pounds of equipment each, sweat accumulating in their suits and under their masks — contemplated scrubbing the dive. Was this finally the end of their luck?